The Visitor:

The Visitor: Writer-director Tom McCarthy follows up his first feature,

The Station Agent, with another impressive effort. Richard Jenkins plays economics professor Walter Vale, a quiet, reserved man who travels down to New York City for a conference. But when he stops off at an apartment he keeps there, he discovers a young immigrant couple living there as an illegal sublet. They didn't know, apologize and leave, but Walter offers to let them stay until they can get things in order. Tarek (Haaz Sleiman), who's Syrian and a very good drummer, is especially grateful, since he has a talent for getting on the wrong side of his girlfriend, Zainab, played by Danai Gurira (Tarek's broad and easy smile also bails him out plenty). As the film progresses, we learn more and more about Walter – he's a widower, his wife was outgoing and well-liked, and he's been stuck in a drab routine. Tarek in particular helps him break out of that rut. We've seen that Walter has no talent for the piano, but he takes much better to the drumming Tarek happily teaches him. Unfortunately, Tarek and Zainab are in the country illegally, and that leads to complications.

The Visitor doesn't wrap up everything tidily, but that's because it's a realistic film.

(And can you imagine all the bad white-guy-ain't-got-no-rhythm jokes some Hollywood films would have?)

The Visitor does a good job of capturing the joy of playing music, and how it and human connection can open a person up. McCarthy, a working actor, gets great, natural performances from everyone (Hiam Abbass as Tarek's mother Mouna is lovely in several later scenes with Walter). The centerpiece of the film, though, is character actor Richard Jenkins' subtle, understated leading turn here, which earned a well-deserved Oscar nomination. If you like this sort of indie film and missed it, do check it out.

(Here's Richard Jenkins on

Fresh Air and on

The Treatment.)

The Dark Knight: Batman Begins

The Dark Knight: Batman Begins may be the best superhero movie ever made, but the same team attempts to one-up themselves with this lengthy, ambitious sequel. Batman/Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) is still fighting crime assisted by loyal butler Alfred (Michael Caine) and technical wizard Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman), but now he has to contend with copycat vigilantes and increasingly desperate criminals. Batman's true love Rachel Dawes (Maggie Gyllenhaal) is now with Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart), Gotham City's upstanding, courageous District Attorney. Along with police detective Jim Gordon (Gary Oldman), they're trying to clean up the city as best they can, but the corruption runs very deep and wide. Into this situation saunters the Joker (Heath Ledger), a genuinely creepy "agent of chaos" who's more intelligent, ruthless, unpredictable and insane than anything they've seen before. He always seems to be a few steps ahead, and both Batman and Harvey Dent are tempted to go to extremes in pursuit of him.

The Dark Knight holds up well to repeated viewings thanks to some spectacular action sequences but also a strong focus on character. I was a bit concerned when I heard Ledger was cast (in some films, he loved to mumble), but every time he's on screen, he's riveting. Similar to Chigurh in

No Country for Old Men, the Joker is unnerving because could snap and kill someone at any moment – although the Joker has much more fun. The unsettling score by Hans Zimmer and James Newton Howard (more in the links below) and vertiginous close-ups are masterful for ratcheting up the tension when the Joker's on-screen. But it's still up to Ledger to sell it, and boy, does he. Katie Holmes wasn't that bad in

Batman Begins as Rachel, but Maggie Gyllenhaal still is quite an upgrade, providing the wit, moxie and vulnerability the role requires. The film presents its heroes with a host of moral dilemmas, mainly due to the Joker's ability to pull off elaborate schemes and willingness not to play by anything approaching the rules. The superhero genre has always held that good vigilantes bend the law but serve justice, yet the

Dark Knight dials up the stakes, and the Joker taunts his pursuers to cross the line in hopes of nabbing him. If

The Dark Knight has any flaws, it's that it seems there's less focus on Wayne/Batman than the Joker and Harvey Dent, or maybe it's just they overshadow him. Also, I wasn't entirely convinced by Dent's shift late in the film, which the last section and the finale depend upon. Christian Bale's raspy Batman voice works great for short lines (especially threats), but becomes a bit unintentionally comic during longer exchanges. Still,

The Dark Knight succeeds as both a blockbuster and a more serious, dramatic film. Writer-Director Christopher Nolan, co-writers Jonathan Nolan and David Goyer and the rest of the team have something good going on, and continue to set the standard the genre will (and should) be judged by.

(SLIGHT SPOILERS)

As if you haven't seen this one! Late in the film, I began to wonder when the hell the Joker found time to wire half the city with explosives. It veers into infallible boogeyman territory. This became more of an issue as

The Dark Knight flirts with the idea that only extremism will defeat the Joker's extremism. If we treat the film as mere escapism, it doesn't matter as much, but the film certainly seems to be asking us to take its moral issues seriously. Predictably, right-wingers

tried to claim the film as their own, and as a validation of George Bush, which was pretty silly. The Batman of

The Dark Knight, like

24's Jack Bauer, is fictional, has nearly infallible judgment and can be trusted with unchecked, awesome powers, and not only takes full responsibility for his actions, he takes the blame for things he didn't do (something the Bush gang and their fans have never done).

The Dark Knight also highlights Batman's transgression in spying on the whole city to find the Joker – Lucius says it's wrong because it's too much power for anyone, and says he'll resign after helping Batman if the system stays. Batman (by wiping the computers at the end) apparently agrees. Batman stops Harvey Dent from torturing and killing a mentally ill member of the Joker's gang, pointing out that it won't accomplish anything (even if it feels satisfying) and will in fact undermine everything good that Dent has done. Batman does lose it himself in beating up the Joker, but gets played in the process (as does one of the cop guarding the Joker). The Joker's plot depends on him making others lose their cool and surrender to fear and rage. Plus, in the end, Batman doesn't break his no killing rule, and brings the Joker to justice. Meanwhile, despite their panic, the citizens (and prisoners) of Gotham on the ferries choose to reject fear and barbarism. As

Rob Vaux puts it:

It's worth noting that the film's most important moment comes not from any of the main characters, but from an unnamed man beneath them played by Tiny Lister. His simple, pointed gesture perfectly encapsulates the need for heroes like Batman, and acts as an all-important reminder in this grim near-masterpiece that everyone is capable of redemption.

(I wondered during the ferry sequence that no one seemed to consider that the Joker would have switched detonators, so that if one group tried to save themselves, they'd actually kill themselves, but that would make the dilemma more of a mind game and less of a moral one.)

All that said, part of me questioned if Dent would really lose it. I bought that he'd kill off crooked cops and criminals, but not that he'd threaten Gordon's family. I also wondered if Batman really had to take the rap for Dent's killings, given the number of scoundrels running around and the enormous body count at that point. In all that chaos, would anyone really question a few more deaths? But Dent's own death would be a bit hard to explain. Yet wouldn't the surviving crooked cop spill the beans anyway? Oh well,

The Dark Knight wants its ending, that of a brooding

Rick Blaine with an armored fist.

There seem to be a few nods to Alan Moore's graphic novel

The Killing Joke. Moore gives us a compelling origin story for the Joker's insanity and the Joker sets out to prove that everyone, given the sufficient push, will go over the edge as he has. Besides sheer chaos, that's the Joker's overall goal in

The Dark Knight, and by capturing the Joker alive, Batman and the good guys refute him. There's another great script choice in the story of the Joker's scars. In Moore's tale, the Joker doesn't have scars, but was driven insane by great personal tragedy (and psychotropic chemicals).

The Dark Knight's Joker flirts with this idea as he explains the origins of his scars to different people, but it seems he ultimately rejects any "reason" for his behavior because he keeps changing the story. He tells it for psychological effect, even as a taunt, not as a confession. It's an inspired device. As the police discover when the Joker's locked up, his real identity is completely unknown, and can't be traced – he's a cipher. He's a truly frightening figure, all the more so because his actions have no discernable motive save wanting "to watch the world burn" (as Alfred puts it), and it seems he's taken this destructive path entirely by choice. (It also made me think of Auden's "The Joker in the Pack" on Iago and

"motiveless malignancy", as well as

another Shakespearean villain who declares, "I should have been that I am, had the maidenliest star in the firmament twinkled on my bastardizing.") Final notes – it's sad to realize that Heath Ledger died so young and with so much promise. The film, and Ledger's acclaim for it, make for fine testaments, although it's doubtless slight comfort to his loved ones.

(Here's Christopher Nolan and Christian Bale on

Fresh Air, and Nolan on

The Treatment. Here's composers Hans Zimmer and James Newton Howard on

Morning Becomes Eclectic. Here's a 1990

Fresh Air interview with Batman creator

Bob Kane.)

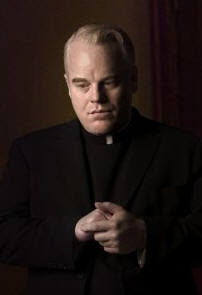

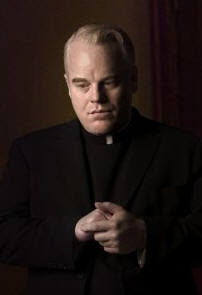

Doubt:

Doubt: John Patrick Shanley directs this adaptation of his own play, with excellent results. It's 1964 at a Catholic school in the Bronx. Sister Aloysius (Meryl Streep) is a hard-nosed, discipline-obsessed head nun, Father Flynn (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is a popular and slightly unconventional new priest, and Sister James (Amy Adams) is a young, idealistic and somewhat naïve nun teaching there. Aloysius doesn't like Flynn, and asks her nuns to keep an eye on him. One day, Father Flynn asks to see one of Sister James' students, Donald Miller, during class, and she notices something's off when Donald returns. Sister James reports it to Sister Aloysius, who fears the worst, and arranges a meeting with Father Flynn. Sister Aloysius is convinced Flynn's molested the boy (although everyone's guarded in their language) and is determined to see him leave. Father Flynn protests his innocence, sometimes forcefully. Sister James is caught in the middle, wanting to believe Flynn but also troubled by misgivings.

What makes

Doubt work well, besides superb performances all around, is Shanley's splendid balancing act of a script, that constantly leaves us in doubt about the central question or at least significant details. The steely Sister Aloysius is quite the battleaxe, and so opposed to change she opposes singing "Frosty the Snowman" at the Christmas pageant because she feels it endorses a pagan belief in magic. Her perception may be heavily skewed because she had to deal with a pedophile priest once before, and so she may be seeing phantoms this time. Her "certainty" sometimes seems to rest on gossamer and prejudice. But she's also a woman in a man's world, and she fiercely protects the nuns in her care. She's also looking out for Donald Miller and the other students, even if her ego's involved as well. She's not a nurturing figure at all, and only has a narrow range as a teacher, that of a strict disciplinarian. But she views herself as the sole defender of tradition, the faith, and decorum, and it's a lonely perch. Some of Father Flynn's explanations makes sense, most of all that Donald's the only black student at school, he's a sensitive kid and having a rough time, and Flynn has been mentoring and protecting him. Father Flynn also wants the school and church to change a bit with the times, and the dour Aloysius just doesn't like him, as Sister James points out.

While the Aloysius-Flynn conflict forms the core of the film (and Streep and Hoffman dive into their battle of wills with relish), the moral center of the film is Sister James. After Flynn's first explanation of his private meeting with Donald, Sister James expresses strong relief, but doesn't fully believe it herself. As Aloysius tells her, "You just want things to be resolved so you can have simplicity back." Sister James is naïve enough to believe a student faking illness to get out school (and no one does guileless like Amy Adams), but she's in tune enough to realize when there's something wrong with her students, such as Donald. (And there's at least one detail she observes that she doesn't share with Aloysius, but later confronts Father Flynn on.) Our sense of what did or didn't happen changes further when Sister Aloysius shares her concerns with Mrs. Miller, Donald's mother (Viola Davis). Mrs. Miller is really only in one substantial scene, but it's a long and remarkable one, filled with shifts and surprises, and basically a short one-act play on its own. I've read that the last exchanges between Sisters Aloysius and James were delivered with a different feel on stage - more ambivalently, I believe. I don't know. But it does seem like Shanley's penned one of his best scripts, possibly a

contemporary classic for the stage. His directing isn't that flashy, but that's fine, and it looks like he was the right choice to direct his own work. The Oscar nomination for his screenplay and the four nominations for acting (even if Hoffman should have been up for lead and not supporting actor) says a great deal about the strength of the material and the skill of the execution.

(SPOILERS)

Did he do it or not? What exactly happened? Is Donald better off if nothing is done, per her mother's request, given his situation? Even if that's the case, would anything excuse Father Flynn's abuse of his position if he did do something? Sister Aloysius' ploy with Father Flynn, the fake out with the phone call, does indeed suggest that something happened at his previous parish. His reaction, of asserting his authority versus arguing the substance of the matter, also supports that. On the other hand, that "something" could have been an affair with a nun or getting drunk or something else disreputable versus molesting a kid. Even the iron-willed Sister Aloysius has her doubts. The school and church will have to change with the times at some point, and that's the greatest loss with Flynn leaving - but he's not the best spokesman for that movement. It's hard to see Flynn leaving as too much of a tragedy - except that he's moving to another parish where, if Aloysius' suspicions are true, the same pattern will likely repeat all over again - especially since, as a modern audience, we know the church history on such things. Even for viewers certain of Flynn's guilt (or innocence), there's plenty to leave one unsettled. I'll be interested in seeing this one again, with the last few scenes in mind, and wish I had seen the original stage production. Sister Aloysius is terrified that if she lets her guard down, civilization will fall, and while she can be something of a bully, there's little question she accomplishes some good. She's clearly stuck in a battle of wills, but there's also principle driving her. I do think the last scene is a bit surprising, but it and the last images have a certain loveliness, because if anyone represents forgiveness, it's Sister James. In the end credits, Shanley thanks Sister James' real-life counterpart (I'm assuming a beloved teacher he had as a kid), and also Cherry Jones, who won a Tony Award for playing Sister Aloysius on stage.

(Here's Philip Seymour Hoffman on

The Treatment, although he's limited in that he can't reveal the central question, which he naturally discussed with Shanley but not the other actors.)

Happy-Go-Lucky:

Happy-Go-Lucky: Mike Leigh delivers another slice-of-life film, this time focused on primary school teacher Poppy, in a wonderful performance by Sally Hawkins. Poppy comes off alternately as a charming free spirit or annoying dingbat. There's little doubt she's got the energy and creativity to be a good teacher to young kids, and she's a loyal friend to her little circle of gal pals, but it's less clear how together she is in the rest of her life. She's not irresponsible as much as a bit naïve and scattered. Or so we think. What makes

Happy-Go-Lucky very interesting is that Poppy has greater depths that aren't immediately apparent, and we slowly glimpse these over time. After her bike is stolen (she didn't bother to lock it up), she starts taking driving lessons, and with her hyperactive laughing and joking is the absolute nemesis of her anal-retentive and bitter instructor, Scott (Eddie Marsan, who's excellent). Their relationship shifts over time, and she also meets a handsome social worker at school she hits it off with.

Her married sister pressures her to settle down, but Poppy insists she's quite happy. As with most Mike Leigh films, the plot is fairly slight, this is more of a character study, and the movie gently ends rather than concludes. But it's very good on those terms. The acting in

Doubt is fantastic but more flashy, with big speeches and more quotable lines. There are some memorable exchanges and moments here, too, but this is more Chekhov and Eric Rohmer than O'Neill and Arthur Miller.

(Here's Sally Hawkins on

The Treatment. I still need to see many of Mike Leigh's films, but I can strongly recommend

Secrets and Lies if you like his style of filmmaking.)

Milk:

Milk: An above-average biopic,

Milk chronicles the life and death of late-bloomer Harvey Milk, the first openly gay politician elected to major office in California, in his case a city supervisor in San Francisco in the late 70s. Director Gus van Sant opens with real news footage of Milk's assassination (and that of mayor George Moscone). At least one reviewer didn't like this device, but I thought it worked pretty well – if you didn't know before, now you knew what was going to happen and the focus was more on how it happened and Milk himself. Milk narrating his story into a tape recorder, interspersed with flashbacks, is a fairly stock device, but was effective (several other screenwriters and directors had failed at making a Milk biopic before writer Dustin Lance Black and van Sant here). All the performances are good, with Emile Hersh as Cleve Jones and Alison Pill as Anne Kronenberg two of the more memorable supporting players. But the key here is Sean Penn, who completely submerges into playing Harvey Milk. He's very convincing, and always interesting to watch. Josh Brolin is also a standout as eventual killer Dan White, another city supervisor all about "family-values." He's wound up extremely tight, the world is changing around him, and he just can't deal with it. While he and Milk initially share an improbable camaraderie, White isn't a natural to political wheeling and dealing, and when he feels betrayed by Milk on a proposal, he takes it very personally.

It's nice to see Milk not portrayed as a saint – he does some double-dealing and maneuvering to try to move things forward and gain more power, and also isn't opposed to outing closeted homosexuals. The film is mostly presented in a realistic and understated way, so during Harvey's death scene, an opera connection thrown in feels forced, jarring, and an unfortunate choice. If (like me) you were pretty young while all this was taking place, the film does a good job as a historical document of the gay rights movement and the progression of civil rights.

Prop. 6, or the "Briggs Initiative," sought to force mandatory firing of any gay schoolteachers or school employees. Footage of Anita Bryant's anti-gay campaign and Walter Cronkite's newscasts from the era are very interesting. It's impossible to watch

Milk without thinking of the recent

Prop. 8 campaign out here in California, and it gives the film an added resonance this year.

(Here's the

Dustin Lance Black and

James Franco segments on

Fresh Air. Here's Josh Brolin with

Rob Vaux. Here's composer Danny Elfman on

Morning Becomes Eclectic.)

The Reader:

The Reader: A German attorney, Michael Berg (Ralph Fiennes), who's successful in his career but emotionally unmoored looks back over his life. David Kross plays the teenage Michael, who definitely does not "meet cute" with the older Hannah Schmitz (Kate Winslet) in 1950s Germany. Nevertheless, they start an affair, which centers in part on Michael reading to Hannah. Michael's madly in love with her, but she suddenly disappears without explanation. As a young law student, he's shocked to discover her as one of the defendants in a trial he attends with his class (it's always nice to see Bruno Ganz, who plays the professor). Michael comes to understand that Hannah kept two important secrets, and this forces him to re-evaluate his entire relationship with her.

I'm wondering how

The Reader will play on a second viewing, and how the story comes across in the original novel. The main problem in the film is that while Michael is clearly struggling, even tormented (and we can understand why), he does little about it. His choice to see Hannah or not during the trial is momentous, but we're never given a clear reason for his eventual decision (and the reason given by David Kross on

Charlie Rose does not play at all – more in the spoiler section). This gives us a rather passive hero, despite all the thematic depth and occasionally arresting and poetic scenes in the movie. The adult Michael finally does take some action, and the sequences with the tapes are a highlight of the movie, but even then, past a certain point he's just paralyzed. Some fear is completely understandable, but considering the dire effects of this whole affair on him, his reticence is harder to comprehend. The key to the film may be in one of the last scenes, between Michael and Ilana Mather (Lena Olin, who's superb). She essentially says there are no pat answers or simple happy endings, and this seems to be a comment on the film itself.

The Reader does explore the power of love, the shock of discovering flaws in the ones we love, the importance of exploring the past, and the dangers of refusing to confront it. I'm just not convinced it's entirely successful at all that. I appreciate its ambition and its occasionally thought-provoking, challenging scenes, but whether it's a matter of the source material or the trials of adaptation, there's a problem in the film in that the hero isn't just reactive versus active, he's not even reactive at times. Still, the performances are very good, and when you know the secrets (unfortunately, I knew them going in, and would recommend you don't if you can help it), you'll pick up on nuances in the performances, especially Kate Winslet's.

(SPOILERS)

I don't think the film asks us to excuse Nazis or even Hannah specifically. Obviously, the Holocaust is a weighty subject, and coming to terms with it has much more significance for Germans. Hannah on trial initially seems bravely frank, but what's disturbing to young Michael, and us, is that Hannah really doesn't seem to understand why the judges and the public are horrified by her. And as the film goes on, it doesn't seem it's a lack of intelligence on her part as much as a moral blind spot and unwillingness to reflect. When adult Michael meets up with older Hannah, she's right about the past being done, but there's just no regret, no moment of asking for forgiveness. It's striking which of her two secrets brought her more shame, and that she went to extraordinary lengths to hide and correct it, but not the more disturbing one. Michael might not have come to terms with his relationship with Hannah, but she sure as hell has not come to terms with her actions in the past. It's a bold story choice in its way, because it doesn't let us forgive Hannah, and doesn't give us a happier ending. But I just wish that scene – and several others - played out a bit longer. It's fine to have a film full of unspoken tensions, but at some point, I do want to hear them spoken. A film that's using Michael as a surrogate for Germany is fine, but only if Michael is a real and compelling character as well. As always, the best way to achieve universality is to go specific. I found myself wondering why Michael had never told anyone about the affair, and why it was so difficult – yes, he clearly felt shame, but he was also a kid at the time. It's also not as if others don't reach out to him and give him the opportunity. There is an implication that Michael's family, and other Germans in his home town, were complicit with the Nazis, which would explain much more, but this isn't made very clear. David Kross said on

Charlie Rose that Michael turns back from seeing Hannah at the prison during the trial because he realizes that revealing her illiteracy would bring her shame. I don't think it plays that way at all – it comes off as cowardice, or some other inexplicable reason. If she begged him not to tell, I could buy his action. But the film doesn't let us in on what's going on with Michael – even a few more close-ups and brief flashbacks would have done the trick, if Kross' description of the intent is accurate. I thought the scene with Lena Olin and Ralph Fiennes was great, all the more so because as Ilana she's not sweet nor forgiving and instead quite challenging. I appreciated her lines about there being no "lesson" to be learned in the concentration camps, which dovetails somewhat with Primo Levi's

The Drowned and the Saved, even though I've met and read accounts by Holocaust survivors whose attitudes are very different. I did think the scenes between Michael and his daughter were quite lovely. It might be interesting to revisit this one down the road.

(Kate Winslet's Oscar win requires another look at

this scene from Ricky Gervais'

Extras. These

two saucy

scenes are also pretty damn funny.)

Revolutionary Road: Revolutionary Road

Revolutionary Road: Revolutionary Road is

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? without the fun, or the happy ending. Well, I'm overstating that – John Givings (Michael Shannon) provides sardonic wit and acid observations as the Fool Who Speaks Truth. But while the craftsmanship here is impeccable, it's produced an awfully bleak picture. Frank Wheeler (Leonardo DiCaprio) and wife April (Kate Winslet) bristle under the constraints of 50s suburban life. She comes up with the idea of moving to Paris, but the romanticism of this plan collides with fear, and Frank suddenly has opportunities opening up at a job he's previously hated. Much of the time they're both miserable, and they often take it out on each other. April gets the worst of it on both counts. They do have tender, passionate and hopeful moments. There are a few transitions that seem to be missing, though, mainly involving April's feelings for Frank, which shift drastically – not that he doesn't give her reason, since he's pretty clueless to callous at times. Their relationship can be tempestuous, but still, looking at them together alone in a bedroom scene, to a countertop scene, to a dining room scene, to a woods scene, to a kitchen breakfast scene – the scenes are good, even remarkable on their own, but feel somewhat disjointed taken as a whole. It's as if some of the bigger events happened off-screen, we've been left out and are now trying catching up.

(I suspect the novel, which is fairly long, has more.) While DiCaprio, Kathy Bates, Michael Shannon and the rest of the cast are all very good, the main reason to see this is Kate Winslet. She's always solid, but this is an especially strong performance. Many of her key moments are just with a look, a shift in expression, and for some of those we can't even see all of her face or her face at all. Beyond that, we've experienced unhappy suburbanites before, from both Winslet and director Sam Mendes. The same goes for Thomas Newman, a fine composer, but his score here reminded me an awful lot of his work on

The Road to Perdition. Roger Deakins' lighting is exceptional, though. (Talk about misleading ads - the late TV spots for this one tried to sell it as an unrestrained, passionate love story, and featured April breathlessly saying, "I felt that way the first time you made love to me." Meanwhile, no wonder the women in the film are unsatisfied – the men of the era have absolutely no sexual stamina!)

Vicky Cristina Barcelona:

Vicky Cristina Barcelona: Woody Allen's latest is an exploration of love, sex and relationships set in lovely Spain. As the narrator tells us, Vicky (Rebecca Hall) and Cristina (Scarlett Johansson) are best friends from America very alike except for their approaches to love. Vicky is practical, and engaged to Doug (Chris Messina), a businessman. Cristina fancies herself passionate and impulsive, and has a strong taste for tempestuous affairs, doomed or not. They receive an offer to spend the summer in Spain from Vicky's relative Judy (Patricia Clarkson) and her husband Mark (Kevin Dunn). At a restaurant, they run into a semi-famous painter, Juan Antonio Gonzalo (Javier Bardem), who's the subject of gossip since not long ago he survived being stabbed by his ex-wife, María Elena (Penélope Cruz). He proposes they fly down to Barcelona with him for the weekend, to see the sights, drink some fine wine, and perhaps make love. (He's actually quite upfront about his intentions.)

Cristina is utterly charmed while Vicky is having none of it, but she goes along in part to chaperone. Juan Antonio is quite the gentleman, but when Cristina falls ill, he and Vicky spend some time together, and to her surprise sparks fly. She's all the more confused when Doug decides to come over to see her in Spain, and discovers more about Judy and her marriage. Meanwhile, Cristina goes off with Juan Antonio. María Elena re-enters the picture with Juan Antonio, and she's one passionate, crazy spitfire. She's about 10% friend, 10% muse, and 80% abusive psychopathic woman you'd best lock the door against and keep away from sharp objects. All the acting's good and the characters are fun, although I still think Cruz' role is the least dimensional and Hall and Johansson give better performances (María Elena just gets some punchier lines). Scarlett Johansson does flirtatious extremely well, but is also allowed to explore more sides of her character later on.

I was quite impressed by Brit Rebecca Hall, since Vicky starts off mostly as a scold, but Hall really sells Vicky's doubts and struggles. What's most enjoyable about

Vicky Cristina Barcelona is that all three main characters discover they're not exactly who they thought they were. Vicky questions her future planned life, Cristina questions how free-spirited she really is, and Juan Antonio questions his inspiration (it's interesting to see him uncertain after being Mr. Smooth earlier on). All become unsure of what they really want, how to get it, and question who they want to and

should wind up with. Even some of the secondary characters go through something similar. Patricia Clarkson only has a few meaty scenes, but she's good as always and as Judy has her own doubts. And Doug alternately seems like an okay, even nice guy and then an unbearable stiff. The predictable parts of

Vicky Cristina Barcelona are nonetheless pleasant, while the many small unexpected turns and touches make it all the more fun (and a bit thought-provoking), up to and including the last few scenes and the ending. This film seemed to receive very divisive reactions critically, but everyone I know who's seen it has liked it. It's probably the best film on love for adults that I saw in 2008.

In Bruges:

In Bruges: Playwright Martin McDonagh moves from his short

Six Shooter to his first feature, an odd couple, gangster film set in... Belgium. Ray (Colin Farrell) accidentally killed an innocent on a recent hit, so his profane, temperamental boss Harry (Ralph Fiennes) has dependable Ken (Brendan Gleeson) take Ray overseas until things cool down, and has them hide out in Bruges. Most of the humor in the film emerges from Ray being a hyperactive city boy, who can't stand being in the quiet, vintage tourist town of Bruges: "Ken, I grew up in Dublin. I love Dublin. If I grew up on a farm, and was retarded, Bruges might impress me but I didn't, so it doesn't." Ken, older, more mature and interested in history, wants to take in the sights and tries to drag Ray along, but Ray's only really interested in getting pissed drunk in the bars. A little excitement comes to town because of a film shoot, which leads to Ray meeting Chloë (Clémence Poésy), a cute local drug dealer, and Jimmy (Jordan Prentice), a little person acting in the film, who Ray insists on calling a midget and who reveals himself as a raging bigot when drunk. But can Ray stay out of trouble? Is someone out to get him? Is there some other reason they've been sent to Bruges? Farrell and Gleeson are fantastic together, and this may be the best Farrell's ever been.

Harry's no fun, but Fiennes seems to be having a blast playing him.

In Bruges does have some tone issues. For the most part, it's an off-beat flick, funny, even goofy, with a dark edge, and highlighting McDonagh's talent for good dialogue and random rants about boring towns and Americans. But other elements are more uneven. Ray is racked by guilt over the accidental murder he committed, and this works pretty well, but parts of the film are surprisingly violent, even gratuitously so. As with some of his plays, McDonagh at times veers toward the gimmicky. It feels at times that he wants to shock or trick the audience members rather than surprise them, delight them and draw them in. That said,

In Bruges is pretty damn entertaining and often inventive, and fans of quirky films with sarcastic characters (and some violence) will really enjoy this one. Here's hoping Martin McDonagh continues to develop his craft and produce more scripts.

Waltz with Bashir (Vals Im Bashir):

Waltz with Bashir (Vals Im Bashir): Ari Folman's film is part autobiography, part investigation into the fluidity of memory, part real life, part dreams and nightmares, and on top of it all, presented in animation. Folman served in Israel's

1982 war with Lebanon as a young man. A friend tells him of a recurring nightmare involving dogs, caused by his own service there. This makes Folman realize he doesn't remember much from that time, including

the massacres at Sabra and Shatila, even though he was in the general area when they happened. "Bashir" refers to

Bashir Gemayel, the president-elect of Lebanon at the time. In most cases, Folman uses the real people portrayed for the audio, and in a few cases got actors to recreate the conversations he had with those people.

Waltz with Bashir is told mostly from the Israeli point of view, and more specifically from the view of Folman, a few friends and others he meets. Still, it achieves a certain universality through its themes of learning the truth about the past, and uncovering and facing disturbing memories. The quality of the animation varies. I found that the drawings were quite good, but the quality of the motion was uneven. At times it's disappointingly minimal, jerky or crude, while at other points it's extremely fluid. The faces during the many talking heads scenes aren't very expressive. With a few notable exceptions, the film is better viewed as stills with motion.

And some of the images are striking and memorable – the opening sequence with snarling dogs, a soldier swimming in the sea at night, a dream of a giant sea-woman, a gunfight in an orchard, and a recurring, disturbing dream Folman has of dead, half-naked young men emerging from the sea at night to face a flaming Beirut. Animation is regrettably often still seen as a kid's medium in America and some other countries, and Folman deserves credit for pushing that (or even exploiting it). The animation serves as a sort of buffering, distancing device to put the viewer at ease and thus delve further on an emotional level. (It made me think of Art Spiegelman's

Maus in that respect, among many other works). I suspect

Waltz with Bashir holds much greater power for those who lived through or remember the events it depicts, or who know more of the history going in. From what I've read, I wasn't as affected overall as other viewers, some of whom who were bowled over. But Folman deserves credit for wrestling with significant stuff and turning the camera on himself. The final sequence is truly brilliant, inspired, powerful and a bit unexpected.

(TomDispatch has excerpts of the graphic novel made of the film – here's

Part 1 and

Part 2.)

Gran Torino:

Gran Torino: Clint Eastwood is Walt Kowalski, a Korean war vet and unrepetant bigot who's just lost his wife, doesn't get along well with his adult children or his grandkids, and isn't too thrilled about the neighborhood's changing demographic. Prickly, he's not shy at all about speaking his mind when prodded, especially to the young, local priest, Father Janovich (Christopher Carley): " I think you're an overeducated 27-year-old virgin who likes to hold the hands of superstitious old ladies and promise them everlasting life." Because it's Eastwood, because of the comedy shock value of him saying clearly inappropriate things, because he's often harshly honest in between the bigotry, and because he does change a bit, it works (although for some viewers, I've heard it's too much). A Hmong family moves in next door, and young, shy Thao (Bee Vang) is being pressured by his cousin to join their gang. As Thao's sister Sue (Ahney Her) tells Walt, all the Hmong girls go to college and the boys go to jail. Thao's initiation is to steal Walt's prized, mint-condition Gran Torino. Needless to say, it doesn't go well. When Walt stands up to the Hmong gang, he becomes an unlikely hero in the neighborhood, and is soon showered with gifts of flowers and food. His racism eases a bit when tempted by the Hmong women's great cooking, and they enjoy a man who appreciates it. Walt also saves Sue from a potentially ugly situation, and she gradually draws him out of his shell. His cultural insensitivities mainly amuse her, and she insists that he is a good man. Walt also becomes an unlikely mentor for Thao. Walt's mentoring is often verbally abusive, but also brutally honest (his advice to the shy Thao about a girl is scathing, hilarious, on-target but also just wrong). However inadvertently, mainly due to his annoyance at Thao, Walt falls into a tough love relationship with him but then shifts to be more genuinely supportive (if still tough). Walt undergoes a gradual, plausible transformation, mainly through dealing with human beings again, and seeing his neighbors as such.

But the Hmong gang is still around, Walt's shown them up, they want revenge and are more than willing to hurt others to get to him. Walt, who's facing health problems and is still awkward with his own family, is determined to fix the situation – and Father Janovich is scared of what that may mean. As Eastwood has in several of his films now (

Unforgiven, Mystic River),

Gran Torino works on its own merits but also serves as a commentary on the many action and revenge films he's made in the past. That dynamic gives the film's ending an added power and poignancy.

Gran Torino exults in the tough guy shtick to a certain degree, but also punctures it, showing the consequences of violence. Some of Walt's more memorable, haunting lines are about the horrors of war and killing. There are some significant flaws to the film, though. Eastwood's squints and growls veer toward caricature at times, and some of young slang dialogue sounds pretty fake and outdated. But the biggest problem is the non-actors (or weak actors) in key roles. Christopher Carley as Father Janovich sometimes seems okay, since the character is clearly outmatched by Walt, but at times the performance just feels weak. Ahney Her as Sue is good when she's bantering with Walt, but she's awful when she's trying to trash talk a couple of gangs. And while Bee Vang's reticence works well for Thao sometimes, he's just not strong. There's a climatic scene between Thao and Walt through a door where Thao's supposed to be upset that's painfully unconvincing, and it really pulls the viewer out and hurts the build to the finale. For all that, if you're an Eastwood fan and won't be completely turned off by the language, this is worth a look.

(The white homeboy-wannabe is Eastwood's son, Scott. Here's Clint Eastwood on

Fresh Air, discussing both

Changeling and

Gran Torino.)

Tropic Thunder:

Tropic Thunder:"A white guy gets an Oscar nomination for playing a black guy? What are we, Hollywood's new retarded?"

- Larry Wilmore about Downey, on The Daily Show.

Tropic Thunder is often crass and dark, but very funny, and you'll know within the first few minutes from its onslaught of fake movie trailers and ads whether its humor is for you. What makes it work is that it makes fun of just about

everybody – Ben Stiller is the action star with pretensions of being a great actor, Robert Downey, Jr. is a "serious" actor who takes his "method" to ridiculous extremes, Jack Black makes really stupid comedies and has a raging drug habit, Brandon T. Jackson is a wannabe gansta, Jay Baruchel is an unassuming sidekick who's smarter than everyone else, Steve Coogan is a director with delusions of grandeur, Matthew McConaughey is a (mostly) amoral Hollywood agent, Tom Cruise is the funniest he's ever been as a profane, dictatorial and

completely amoral studio exec with a taste for club dancing, and Nick Nolte is seriously crazy and calls into question the whole faux-authenticity, "based on a true story" thing. The two most dicey gags work because they're mocked in the film itself. Downey's character Kirk Lazarus is playing a black man in black face, but Jackson as Alpa Chino is constantly ragging on him for actually thinking he's black. Ben Stiller's Tugg Speedman previously tried to make his mark as a serious actor in

Simple Ben as a mentally challenged young man, but it failed to earn praise. There's actually a bit too much of Simple Ben for my tastes, but Downey/Kirk has a celebrated monologue where he explains to Tugg that his mistake was in going "full retard."

It's hilarious because it's completely true. It's mocking Hollywood, not mentally challenged people (but I know some viewers felt hurt or offended, I'm sympathetic to that, and they're entitled to their reaction). Downey apparently stays true to his word (as Kirk Lazarus) and in the

Spinal Tap tradition stays in character for the

Tropic Thunder DVD commentary. Some of the web promo ads for the film were very funny, and writer-director-star Ben Stiller deserves credit for casting himself as the ass and actually delivering a comedy that makes people laugh. Like I said, this is not for all tastes – know yours and seek it out or avoid it, accordingly.

(Here's Ben Stiller on

The Treatment.)

Hamlet 2:

Hamlet 2:"It was stupid!"

"It was stupid, but it was also theater."

2008 was a banner year for Steve Coogan. Here, he plays Dana Marschz, an inept high school drama teacher in Tucson, Arizona, who seeks to save his imperiled program by staging a triumphant production. Rather than staging scenes from recent movies as he usually does, he's convinced by the school newspaper's diminutive, acid-penned but insightful critic to put on an original production. Dana decides to write and direct – Hamlet 2. "Doesn't everybody die at the end of the first one?" asks wife Brie (Catherine Keener). "I have a device," he replies. And boy, does he ever. Dana is not a good actor, and he's a pretty bad teacher, too, but for all that, he's tremendously dedicated, and the kids in his class who mock him respond gradually to that over time.

Elisabeth Shue plays herself in a funny part (she's a good sport, and it's a great career move). The irrepressible Amy Poehler enters late as a profane firecracker of a civil rights attorney, Cricket Feldstein, who has some pronounced personal issues but is determined that the show must go on. And the big show itself winds up being surprisingly effective – stupid, but also theater.

Hamlet 2 would make a great double-bill with

Waiting for Guffman, and "Rock Me, Sexy Jesus" and another song that shall remain nameless (it'd spoil the gag) also leave their, um, mark.

(Here's director Andrew Fleming and producer Pam Brady (they co-wrote the movie together) on

Fresh Air.)

Trouble the Water:

Trouble the Water: This Oscar-nominated documentary centers on Hurricane Katrina. From my

earlier post on it:

Kimberly Rivers Roberts and her husband Scott, residents of New Orleans' lower 9th Ward, were there when Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005. Kimberly got a video camera shortly before, and she documented what happened to them... it's powerful stuff.

The film intercuts Kim Roberts' footage with news footage from the time, and the filmmakers film the Roberts throughout their long trek, checking in with them periodically up to roughly the present. The government indifference and incompetence on display is infuriating. The 9/11 calls, and other moments, are heart-breaking. But there are also some pretty inspiring moments, too — from the Roberts, from the people they huddle in an attic with as the water rises in their homes, from a heroic neighbor. The survivors have been treated very poorly, but they're very appreciative toward the National Guard when they finally show up, and they buoy each other through camaraderie, faith, humor, and in at least one case, music. There are too many striking moments to name them all, and I wouldn't want to spoil them, but two involve the camera just staying on Kimberly – recovering a photo from their devastated home, and performing a rap she's recorded.

Do seek this one out. Normally, all the documentary nominees are great, but it's hard to see them in the theaters. Thank goodness for rental services...

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button:

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button: Benjamin Button (Brad Pitt) curiously ages in reverse, learning something about the mysteries of life and love in the process. Although I think

Benjamin Button received far more acclaim than it deserved, I did think it was good. There's a sincerity to the love story and a lyricism to the filmmaking that gave its ending poignancy. Its technical wizardry is impressive, and director David Fincher remains a meticulous director. That said, it's a long film that feels that way, and while I'm glad I saw it, it's not one I'd rush out to see again. There are also some inherent challenges to the story, and some snags in the storytelling. Its premise is fantastical – someone aging in reverse. I think that's sold pretty well, but much of our interest in the film derives from simply seeing how exactly that's going to play out. How is such a person born? How will he die? The film shows an interesting passage through history, but the structure is very episodic, and Benjamin pretty much just goes with the flow, making him a rather bland character. Cate Blanchett's very good as Daisy, the great love of Benjamin's life, and Taraji P. Henson's the strongest of a solid supporting cast as Queenie, Benjamin's accepting and loving adoptive mother.

(Definitely watch

"The Curious Case of Forrest Gump" if you haven't seen it yet. Here's David Fincher on

The Treatment. Here's composer Alexandre Desplat on

Morning Becomes Eclectic. D.C.'s own

Taraji P. Henson gave a short interview to

The Washington Post.)

Frost/Nixon:

Frost/Nixon: Adapted by Peter Morgan from his own stage play and one of director Ron Howard's better efforts,

Frost/Nixon is a dramatization of David Frost's series of interviews in 1977 with the infamous president, post-resignation. I was a bit wary of this film going in, because it can be hard to buy an actor playing such a well-known figure, and why not just watch the actual interviews? Wouldn't a documentary be a better route for this material? And how will all of this of this play with a younger audience less familiar with Watergate? But it works quite well. Nixon, played with towering physicality, insinuating menace and deceptive charm by Frank Langella, consults with his handlers, chief among them Jack Brennan (Kevin Bacon) and Swifty Lazar (Toby Jones). They view entertainment interviewer and tabloid playboy David Frost as a lightweight, and the perfect vehicle for Nixon to rehabilitate his image and revise his historical legacy. The big paycheck also helps. Frost (Michael Sheen) knows television spectacle, but he

is something of a lightweight – and is pushed to delve, push and research by his team, most of all Bob Zelnick (Oliver Platt) and James Reston (Sam Rockwell).

But Nixon is nothing if not wily – and it's only with a drunken late-night call before the final, crucial interview segment on Watergate that Frost gets a more unvarnished glimpse at what really makes Nixon tick, and his own similarities (and differences) from the disgraced ex-president. What the film does better than the successful play (so I've read) is its extensive use of the close-up. We see Nixon sweating, and we see his "you can't handle the truth" moments where he reveals his true feelings in all their ugly glory. Both Langella and Sheen are very good, as is the entire cast. Platt and Rockwell are always a joy to watch, and they riff off each other here wonderfully. Rebecca Hall, playing Frost's latest girlfriend, doesn't have that much to do but does it well nonetheless (Hall said she enjoyed playing a sexy part for a change). And Bacon and Langella actually generate some sympathy for Nixon.

I'm interested to learn more about how accurate the film is (the DVD will likely supply some good material, and the links I've included below help). I do agree that it would be a mistake to think that Nixon really did receive "the trial he never had" and that he was effectively brought to justice, or that the evil that he did was interred with his bones. (There's a whole cohort of movement conservatives who viewed Nixon's great crime as getting

caught, and they went on to perpetrate Iran-Contra and to serve in the Bush administration. Also, the film presents one lie unchallenged - Gerald Ford deceiving Congress, telling them "There was no deal" but not mentioning that Nixon's Chief of Staff Al Haig offered Ford a deal. More on that below.) Still,

Frost/Nixon deserves credit for tackling some weighty and timely issues, such as accountability for those in power, the responsibilities of journalists and the general public, and the potential power of the unblinking camera.

(Here's Ron Howard on

The Treatment. James Reston, Jr. gives good background on the real events on

Fresh Air. Rick Perlstein, author of

Nixonland, explains how Nixon's relationship with TV

changed over time, and is one of several Nixon experts weighing in on the film at

The Guardian. More on Ford and the Nixon deal

here.)

As always, the fun in watching the Oscars lies in mocking the excesses, booing the injustices, and cheering on the worthy winners. Hugh Jackman did a good job overall as Oscar host. Consensus at the Oscar party I attended was that not being a comedian helped him. He didn't need to come out and deliver a real comedy set, as other hosts have. There was much less pressure on him to be funny (although he was at points); he just needed to be charming, which he handled with ease. If all else failed, he could just say, "Meryl Streep, ladies and gentlemen!" as he did a couple of times. But his opening number was lively and creative, with some good gags – singing to Kate Winslet about swimming in excrement, joking about renting The Reader, and making Anne Hathaway surely the prettiest actor ever to play Richard Nixon. Despite the immense venue, the staging was very intimate, at least for Jackman and the acting nominees in the first few rows. (But where was Jack Nicholson? Isn't this the second Oscar ceremony in a row without the King of Hollywood? I also see I shouldn't have cut the "Aniston to Jolie and vice versa reaction shot" category from the Oscar Drinking Game.)

As always, the fun in watching the Oscars lies in mocking the excesses, booing the injustices, and cheering on the worthy winners. Hugh Jackman did a good job overall as Oscar host. Consensus at the Oscar party I attended was that not being a comedian helped him. He didn't need to come out and deliver a real comedy set, as other hosts have. There was much less pressure on him to be funny (although he was at points); he just needed to be charming, which he handled with ease. If all else failed, he could just say, "Meryl Streep, ladies and gentlemen!" as he did a couple of times. But his opening number was lively and creative, with some good gags – singing to Kate Winslet about swimming in excrement, joking about renting The Reader, and making Anne Hathaway surely the prettiest actor ever to play Richard Nixon. Despite the immense venue, the staging was very intimate, at least for Jackman and the acting nominees in the first few rows. (But where was Jack Nicholson? Isn't this the second Oscar ceremony in a row without the King of Hollywood? I also see I shouldn't have cut the "Aniston to Jolie and vice versa reaction shot" category from the Oscar Drinking Game.)  On the music front, this was a strong year. I was happy to see A. R. Rahman's wins for his energetic, infectious score and song-writing, especially because they played such an important role in Slumdog Millionaire. He was certainly the most original choice for the Academy. Danny Elfman's score for Milk was quite good, and Thomas Newman continues to show why he's one of the best out there with his soaring work on WALL-E. Apparently, there was an eligibility issue for the score for The Dark Knight by James Newton Howard and Hans Zimmer. Their Joker's theme, using a single, extended cello note, was eerie and extremely effective (more in the Dark Knight entry below). For the songs, no nomination for Hamlet 2's "Rock Me, Sexy Jesus" was unfair but unsurprising, while not including Bruce Springsteen's "The Wrestler" was a glaring omission. It and two of the actual nominees provided the capstones to their respective films. Normally, I'd be pulling for my man Peter Gabriel to win, and his song "Down to Earth" offered a nice exit for WALL-E. But "Jai Ho" from Slumdog was a celebratory explosion for that film, so it deserved the edge. Still, I think even "Jai Ho" paled to the role Springsteen's "The Wrestler" played for its movie – a haunting, simple soliloquy that put the entire preceding film in perspective and lingered far after.

On the music front, this was a strong year. I was happy to see A. R. Rahman's wins for his energetic, infectious score and song-writing, especially because they played such an important role in Slumdog Millionaire. He was certainly the most original choice for the Academy. Danny Elfman's score for Milk was quite good, and Thomas Newman continues to show why he's one of the best out there with his soaring work on WALL-E. Apparently, there was an eligibility issue for the score for The Dark Knight by James Newton Howard and Hans Zimmer. Their Joker's theme, using a single, extended cello note, was eerie and extremely effective (more in the Dark Knight entry below). For the songs, no nomination for Hamlet 2's "Rock Me, Sexy Jesus" was unfair but unsurprising, while not including Bruce Springsteen's "The Wrestler" was a glaring omission. It and two of the actual nominees provided the capstones to their respective films. Normally, I'd be pulling for my man Peter Gabriel to win, and his song "Down to Earth" offered a nice exit for WALL-E. But "Jai Ho" from Slumdog was a celebratory explosion for that film, so it deserved the edge. Still, I think even "Jai Ho" paled to the role Springsteen's "The Wrestler" played for its movie – a haunting, simple soliloquy that put the entire preceding film in perspective and lingered far after.  The most welcome award was the always good and versatile Kate Winslet finally winning her Oscar. Her warm shout-outs to deceased Reader producers Anthony Minghella and Sydney Pollack were especially nice, and the requested whistle from her father was fantastic. (I would have liked to have seen Sally Hawkins get a nomination for Happy-Go-Lucky, though.) Heath Ledger's untimely death locked in his win, but it was a remarkable performance, and his family's acceptance was one of the most emotional moments of the evening. I thought Penelope Cruz was the least deserving of the Best Supporting Actress nominees, and won mainly due to past nominations (as is often the case). Cruz serves ably in Vicky Cristina Barcelona, but it's a performance consisting of only a few notes, and mostly one ("feisty senorita," as a friend of mine put it). Both Scarlett Johansson and Rebecca Hall deliver better performances in the same film. I'd have given the award to the multitalented, always superb Amy Adams, who had the most screen time and the most substantial performance of the lot. I would have been satisfied with any of the other nominees winning, too. Viola Davis really only has one scene, but it's a long one, full of shifts and discovery, and she's fantastic in it. Taraji P. Henson is very good in Benjamin Button (several people were shocked to discover that the young Henson, looking gorgeous at the Oscars, played Queenie in the film). And Marisa Tomei gives a layered performance that moves her role in The Wrestler away from that beloved Oscar trope, the stripper (or prostitute) with a heart of gold. For Best Actor, I would have been happy with either Sean Penn or Mickey Rourke winning, but would have given the edge to Rourke on the merits and because Penn's already won. (I would have really cheered for Richard Jenkins – and while Brad Pitt deserved his nomination for 12 Monkeys, I don't think he merited one for Benjamin Button.) The debate among our crew was on the tipping points – what role was played by lingering resentments toward Rourke in Hollywood, and extra support for Penn because of Prop. 8? Was this also delayed appreciation for Brokeback Mountain? Rourke said he wanted Penn to win, since he was a good friend to him during his dark days. Rourke did get several nice shout-outs at the awards, and his rambling, profanity-laced acceptance speech at the Independent Spirit Awards is pretty entertaining. So he's gotten his moment, his "return to the ring," as Ben Kingsley put it. And Penn did do a terrific job, submerging himself into the role of Harvey Milk. As with Meryl Streep, it's easy to take him for granted because he's always good (I know people who think of him as a scenery-chewer, but he's not in Milk). Penn's speech was unsurprisingly political but on-target, and also fairly funny and restrained for him. (It was hard not to like "You commie, homo-loving sons of guns" – but dude, remember to thank your wife!)

The most welcome award was the always good and versatile Kate Winslet finally winning her Oscar. Her warm shout-outs to deceased Reader producers Anthony Minghella and Sydney Pollack were especially nice, and the requested whistle from her father was fantastic. (I would have liked to have seen Sally Hawkins get a nomination for Happy-Go-Lucky, though.) Heath Ledger's untimely death locked in his win, but it was a remarkable performance, and his family's acceptance was one of the most emotional moments of the evening. I thought Penelope Cruz was the least deserving of the Best Supporting Actress nominees, and won mainly due to past nominations (as is often the case). Cruz serves ably in Vicky Cristina Barcelona, but it's a performance consisting of only a few notes, and mostly one ("feisty senorita," as a friend of mine put it). Both Scarlett Johansson and Rebecca Hall deliver better performances in the same film. I'd have given the award to the multitalented, always superb Amy Adams, who had the most screen time and the most substantial performance of the lot. I would have been satisfied with any of the other nominees winning, too. Viola Davis really only has one scene, but it's a long one, full of shifts and discovery, and she's fantastic in it. Taraji P. Henson is very good in Benjamin Button (several people were shocked to discover that the young Henson, looking gorgeous at the Oscars, played Queenie in the film). And Marisa Tomei gives a layered performance that moves her role in The Wrestler away from that beloved Oscar trope, the stripper (or prostitute) with a heart of gold. For Best Actor, I would have been happy with either Sean Penn or Mickey Rourke winning, but would have given the edge to Rourke on the merits and because Penn's already won. (I would have really cheered for Richard Jenkins – and while Brad Pitt deserved his nomination for 12 Monkeys, I don't think he merited one for Benjamin Button.) The debate among our crew was on the tipping points – what role was played by lingering resentments toward Rourke in Hollywood, and extra support for Penn because of Prop. 8? Was this also delayed appreciation for Brokeback Mountain? Rourke said he wanted Penn to win, since he was a good friend to him during his dark days. Rourke did get several nice shout-outs at the awards, and his rambling, profanity-laced acceptance speech at the Independent Spirit Awards is pretty entertaining. So he's gotten his moment, his "return to the ring," as Ben Kingsley put it. And Penn did do a terrific job, submerging himself into the role of Harvey Milk. As with Meryl Streep, it's easy to take him for granted because he's always good (I know people who think of him as a scenery-chewer, but he's not in Milk). Penn's speech was unsurprisingly political but on-target, and also fairly funny and restrained for him. (It was hard not to like "You commie, homo-loving sons of guns" – but dude, remember to thank your wife!)  I'd have given the endlessly inventive and elegant WALL-E best original screenplay, but Dustin Lance Black's winning script for Milk was solid and above average for a biopic, and he gave one of the most heartfelt, memorable speeches of the night. Manic leprechaun Danny Boyle gave a sweet speech after winning Best Director, and his apology to the choreographer was classy (it's very easy to leave someone out of the credits, especially on a major production). Tina Fey and Steve Martin, both writers and witty performers, made the screenplay presentations the most entertaining of the night. The device of showing some of the script and the film was last done (to my memory) in 2002 (In the Bedroom, Fellowship of the Ring), and it works wonderfully, so I hope it endures this time (something similar for the sound awards would be harder, but fantastic). Jack Black was very funny presenting, joking about making his money by working for Dreamworks Animation but betting on Pixar, and claiming he only watched movies with himself in it – like most actors. Ben Stiller's Joaquin Phoenix impression was pretty funny, although he let it go on a bit too long, so that the names of the cinematography nominees were obscured by laughter. Queen Latifah did a really lovely job singing "I’ll be Seeing You” during the "In Memoriam" section, although the camera cutting was excessive.

I'd have given the endlessly inventive and elegant WALL-E best original screenplay, but Dustin Lance Black's winning script for Milk was solid and above average for a biopic, and he gave one of the most heartfelt, memorable speeches of the night. Manic leprechaun Danny Boyle gave a sweet speech after winning Best Director, and his apology to the choreographer was classy (it's very easy to leave someone out of the credits, especially on a major production). Tina Fey and Steve Martin, both writers and witty performers, made the screenplay presentations the most entertaining of the night. The device of showing some of the script and the film was last done (to my memory) in 2002 (In the Bedroom, Fellowship of the Ring), and it works wonderfully, so I hope it endures this time (something similar for the sound awards would be harder, but fantastic). Jack Black was very funny presenting, joking about making his money by working for Dreamworks Animation but betting on Pixar, and claiming he only watched movies with himself in it – like most actors. Ben Stiller's Joaquin Phoenix impression was pretty funny, although he let it go on a bit too long, so that the names of the cinematography nominees were obscured by laughter. Queen Latifah did a really lovely job singing "I’ll be Seeing You” during the "In Memoriam" section, although the camera cutting was excessive. The Paul Newman clip was a perfect closer, though (Heath Ledger was featured last year, if you missed it, and they added Roy Scheider this year after forgetting him last time). Man on Wire star Philippe Petit provided some fun balancing an Oscar on his chin and performing a magic trick. Best Animated Short winner Kunio Katô's speech in halting English, unexpectedly closing with "Domo Arigato, Mr. Roboto," might have been the funniest (and most unexpected) bit of the night.

The Paul Newman clip was a perfect closer, though (Heath Ledger was featured last year, if you missed it, and they added Roy Scheider this year after forgetting him last time). Man on Wire star Philippe Petit provided some fun balancing an Oscar on his chin and performing a magic trick. Best Animated Short winner Kunio Katô's speech in halting English, unexpectedly closing with "Domo Arigato, Mr. Roboto," might have been the funniest (and most unexpected) bit of the night. On the critic front - a pet peeve of mine with "best of" lists is when critics are late to the party and list films that came out the previous calendar year with no acknowledgement of that fact. I know most critics are expected to deliver such lists before the end of a calendar year, or not long into the new year, and the Oscar bait deluge can make it hard to see everything before deadlines. Generally, it's especially difficult with the major foreign films. I have an advantage with my roundups of having the extra two months before the Oscars to catch up, and almost everything will be out by then. But many reviewers have access to free screenings and/or screener DVDs. For American critics, it's ridiculous to say There Will be Blood was one of the best films of 2008. The same goes for The Counterfeiters, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and Four Months, Three Weeks, Two Days, when all were in major award contention as 2007 films, and The Counterfeiters won the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. A critic in a fairly prominent publication named The Lives of Others his best film of 2007, when it was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film of 2006 – and won. Did these critics (who shall remain nameless) miss all this? The worst remains listing There Will Be Blood for 2008 - seriously, Daniel Day Lewis accepting his Best Actor award wasn't a clue you're a year late? Just add a special note to the list, and by all means honor a good film or two you missed earlier, since highlighting good work is one of the key reasons to review films in the first place. Plenty of critics add such notes and also list honorable mentions. Another solution for more casual reviewers is simply to list 'the best films I've seen this year,' rather than describing (for instance) 2007's The Diving Bell… as one of 'the best films of 2008' in December 2008. It's just that it's jarring when said film was already being discussed at some length 10-14 months ago (it was in limited release, reviewed, on many 2007 lists, discussed on Charlie Rose etc.). It's a bit like talking to football fans, praising the New York Giants' great Super Bowl win, and wondering aloud if they'll repeat this year. Where were you? (For foreign films released in America a year/years later, I try to include the original release date, too.) Of course, since the biggest troublemakers are foreign-language films, maybe I'm being unfair on the front. With There Will Be Blood, I've been told the studio was uncooperative about showing it to some reviewers, and that cost the studio. Still, it just looks ridiculous to list such a celebrated film a year later - and as the fourth best film of 2008. Oh, and naming as your top film of the year something you and fewer than a dozen people saw at a private residence does not give you indie cred; it just means you're really obnoxious (I have actually seen that done, a few years back).

On the critic front - a pet peeve of mine with "best of" lists is when critics are late to the party and list films that came out the previous calendar year with no acknowledgement of that fact. I know most critics are expected to deliver such lists before the end of a calendar year, or not long into the new year, and the Oscar bait deluge can make it hard to see everything before deadlines. Generally, it's especially difficult with the major foreign films. I have an advantage with my roundups of having the extra two months before the Oscars to catch up, and almost everything will be out by then. But many reviewers have access to free screenings and/or screener DVDs. For American critics, it's ridiculous to say There Will be Blood was one of the best films of 2008. The same goes for The Counterfeiters, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and Four Months, Three Weeks, Two Days, when all were in major award contention as 2007 films, and The Counterfeiters won the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. A critic in a fairly prominent publication named The Lives of Others his best film of 2007, when it was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film of 2006 – and won. Did these critics (who shall remain nameless) miss all this? The worst remains listing There Will Be Blood for 2008 - seriously, Daniel Day Lewis accepting his Best Actor award wasn't a clue you're a year late? Just add a special note to the list, and by all means honor a good film or two you missed earlier, since highlighting good work is one of the key reasons to review films in the first place. Plenty of critics add such notes and also list honorable mentions. Another solution for more casual reviewers is simply to list 'the best films I've seen this year,' rather than describing (for instance) 2007's The Diving Bell… as one of 'the best films of 2008' in December 2008. It's just that it's jarring when said film was already being discussed at some length 10-14 months ago (it was in limited release, reviewed, on many 2007 lists, discussed on Charlie Rose etc.). It's a bit like talking to football fans, praising the New York Giants' great Super Bowl win, and wondering aloud if they'll repeat this year. Where were you? (For foreign films released in America a year/years later, I try to include the original release date, too.) Of course, since the biggest troublemakers are foreign-language films, maybe I'm being unfair on the front. With There Will Be Blood, I've been told the studio was uncooperative about showing it to some reviewers, and that cost the studio. Still, it just looks ridiculous to list such a celebrated film a year later - and as the fourth best film of 2008. Oh, and naming as your top film of the year something you and fewer than a dozen people saw at a private residence does not give you indie cred; it just means you're really obnoxious (I have actually seen that done, a few years back).